Above photo credit: 11/3/1945 WAR DOGS RETURN… First members of infantry scout dog platoons to arrive from overseas get back their land legs by limbering up with their masters, as this one does here. He returned with over 90 dogs that served wth the 5th Army in Italy. (Getty Images)

Article by Lishamarie Hunter

Man’s best friend.

Call ‘em what you want — war dogs or military working dogs — they have been around for centuries worldwide. The states had an unofficial canine war force in World War I, but military dogs did not become officially recognized until March 13, 1942, when a private organization, Dogs for Defense was established to recruit the public’s dogs for the U.S. military’s War Dog Program, known as the K-9 Corps.

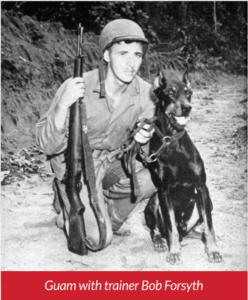

WWII in the Pacific theater, Doberman Pinschers served as sentries, scouts, and messengers.

It quickly became apparent there would not be enough of those breed of dogs to meet the demand. They opened up the field to include 30 breeds, led by Airedale Terriers, Boxers, Labrador Retrievers, German Shepherd Dogs, and Saint Bernards. American donors were given a certificate by the government as a means of thanks for their “patriotic duty.” Dogs were immediately sent into training, where some excelled and others didn’t. Wash-outs were returned to their owners; those who passed were eventually sent into battle from foxholes to beach fronts, where they were utilized for messenger, mine-detection, sentry and scout duties.

Eventually, the military began training its own dogs, but by the war’s end, Dogs for Defense procured approximately 18,000 of the 20,000 dogs. One famous furry warrior was Chips. Chip was a German Shepard/Husky mix was credited with saving many United States soldiers lives. Chip earned a Purple Heart and Silver Star. This German Shepherd mix, one of the most famous combat canines of World War II, once conducted a daring raid on a sniper nest in Sicily, breaking away from his handler and capturing four enemy soldiers.

Eventually, the military began training its own dogs, but by the war’s end, Dogs for Defense procured approximately 18,000 of the 20,000 dogs. One famous furry warrior was Chips. Chip was a German Shepard/Husky mix was credited with saving many United States soldiers lives. Chip earned a Purple Heart and Silver Star. This German Shepherd mix, one of the most famous combat canines of World War II, once conducted a daring raid on a sniper nest in Sicily, breaking away from his handler and capturing four enemy soldiers.

Five years after WWII, the Korean Conflict triggered the need for military working dogs again. They were chiefly deployed on combat night patrols and were detested by the North Koreans and Chinese because of their ability to ambush snipers, penetrate enemy lines and scent out enemy positions. It reached a point where reports noted the foes were using loudspeakers saying, “Yankee, take your dog and go home!” The dogs were chiefly used to patrol air base perimeters and guarding bomb dumps.

Fast forward to Vietnam – a totally new environment and job description for these “fur missiles,” as some military dog handlers described them. In a terrific chronology, Their duties were widespread – scout, sentry, patrol, mine and booby-trap detection, water and combat. The Viet Cong hated the dogs so intensely they put $20,000 bounty for their capture. These dogs walked sentry and alerted the service members to many Viet Cong ambushes. An estimated 4,000 dogs and 9,000 military-dog handlers served in Vietnam.

During the evacuation of Vietnam, the military working dogs that served our forces and saved many service members lives were left behind. They were classified as “surplus equipment.” Many handlers were willing to pay their dog’s flight home, the military would not allow them to do so. During this time some were transferred to the South Vietnamese military and police units who were not trained to handle them and others were euthanized. It is estimated that of 4,000 that served, fewer than 200 made it back to the U.S. Because of this in 2000 Congress passed the “Robby Law” allowing other law enforcement agencies to adopt the dogs.

In stark contrast to Vietnam, the hot, dusty environments of Iraq and Afghanistan serve up a new set of challenges for military working dogs trained for explosive and drug detection, sentry, therapy and service. Cairo, a Belgian Malinois, was a member of Seal Team Six that killed Osama bin Laden. A new breed of elite canine soldier, a Special Forces dog’s training covers such skills as bomb-sniffing and parachuting from helicopters.

Dogs’ sense of smell is roughly 50 times better than ours, meaning they can sniff out IEDs before they detonate and injure or kill U.S. servicemen in the prolonged Iraq and Afghanistan conflicts.

Ground patrols are able to uncover only 50 percent of these, but with dogs, the detection rate increases to 80 percent, claims the Defense Department. According to retired Air Force K9 handler, Louis Robinson, a fully trained bomb detection canine is likely worth over $150,000, and considering the lives it may save, you could characterize it as priceless.

Read more articles from VOM Magazine here: https://www.veteransoutreachministries.org/vom-magazine/