A Series by Lishamarie Hunter

Unique Challenges

The past two articles that I have written provided a chronological timeline of how women have served this nation’s military, starting with the Revolutionary War up to today’s modern conflicts. The growing number of women who are serving has increased from four percent in the 60’s to fifteen percent in 2015, and is excepted to increase throughout the following years.

This year West Point Military Academy saw a historical number of women enter and graduate from the institute. There are 2.2 million women veterans in the United States and they make up 10% of overall veteran population. The issues that affect these service members are unique to their gender.

One statistic states that female veterans have a 250% greater risk of suicide than civilian women. Women feel invisible, disconnected and isolated after leaving the military. Many female veterans have been misdiagnosed with bi-polar disorder, chronic depressed or having hormonal issues when they are actually struggling with MST/PTS (military sexual trauma, and or post traumatic stress). These experiences create issues with reintegration into civilian life.

Many female veteran do not identify as veterans. They often feel betrayed by the institution and do not want anything to to do with it. Statistics state that 90% of the females who have served has experienced being sexual harassed. Several have said they don’t identify because they did not fight in a combat zone or because they served during peace time, therefore, do not feel they deserve the acknowledgement of being a veteran.

By not identifying as a veteran many have missed out on the benefits and resources that would have assisted in their transition process. The Department of Veterans Affair, over the past couple of years have greatly improved the process for veterans to request and receive their benefit.

In its 2017 Annual Homeless Assessment Report to Congress, the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) estimated that just over 40,000 veterans were homeless on a single night in January of that year. Of those, about 9% were women. From 2016 to 2017, the number of homeless female veterans increased by 7%, compared with 1% for their male counterparts. Returning women are 4 times as likely as male veterans to become homeless. One problem, unique to homeless female veterans, is that many have children. The institutions that provide assistance to homeless veterans often times do not have enough resources for the female veteran and their families.

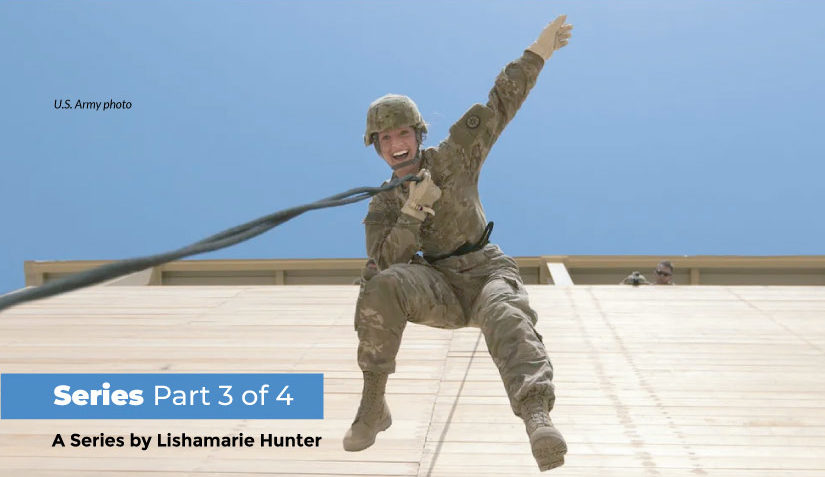

While serving most women are the minority, often times they are the only female in their section. Many believe they must constantly prove themselves. In the service and out many females face challenges to their ability to preform their jobs; female mechanic have been made to work administrative positions. When they leave the service often times they are challenged on their vet status.

Two female veterans relayed their story about how one afternoon they parked in a disabled veterans parking space. When they got out of the vehicle an elderly gentleman confronted them, “that is for veterans!” She replied “I know”. He continued and followed her into the business where he wanted to know why she thought she could park there. She finally showed him her VA Healthcare card. He turned and left.

An article, 5 Things Women Veterans Want Everyone To Know, written by Goldstein in 2017 found that regardless of the person’s rank, branch of service, ethnicity or age women who had served wanted to have their service recognized not challenged or intoned They did not want the people who were suppose to provide healthcare and mental health to over look their service and sacrifice.

The majority of the women interviewed expressed exhaustion with the fact that “approximately 15% of all active duty forces are women and 20% of new enlistments are also women, yet are underrepresented and under resourced.

Even though women have served since the Revolutionary War, it was not until 1988 that the VA began offering medical and mental health to female veterans. It was described by a VA clinic manger from Salt Lake City calls it “the legacy of that exclusion is still being felt today.”

Many women do not want to be treated differently but they want their experience to be taken in to consideration, when receiving services from institution who are supposed to provide care for them. The one message that was very clear when researching and interviewing people for this subject was “A Veteran is a Veteran.”